Marked for Life Myanmarã¢â‚¬â„¢s Chin Women and Their Facial Tattoos Review

Marked for Life

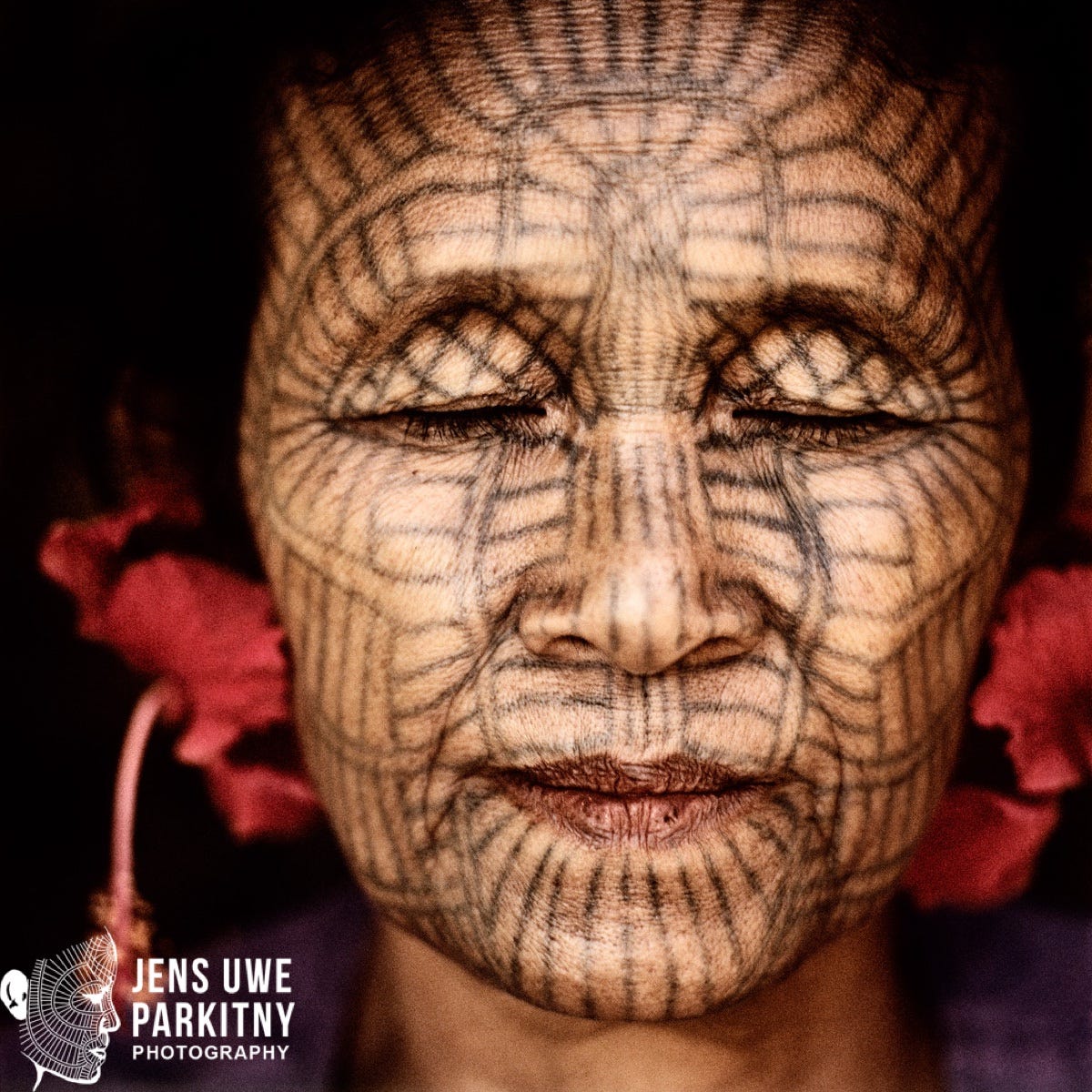

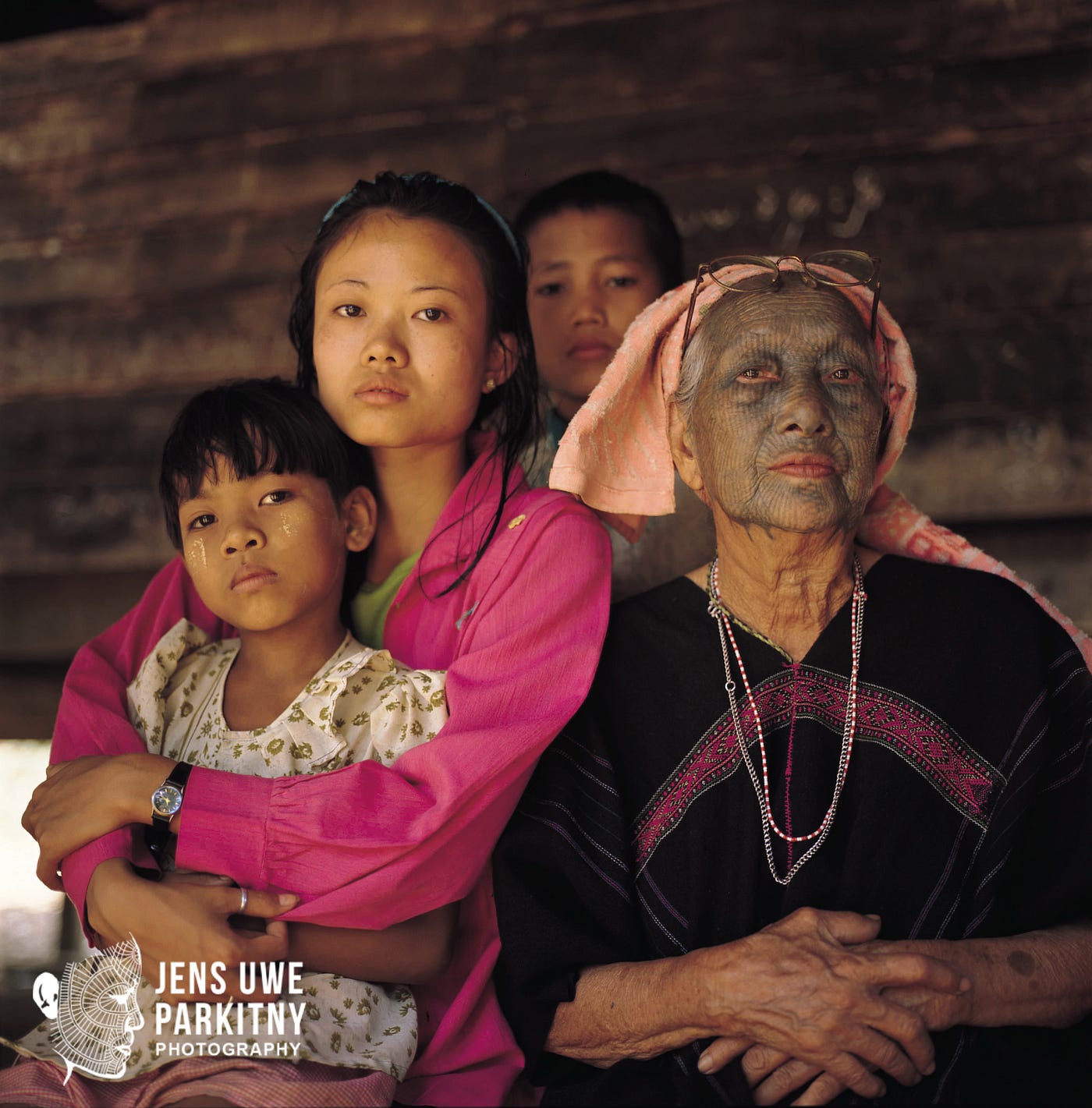

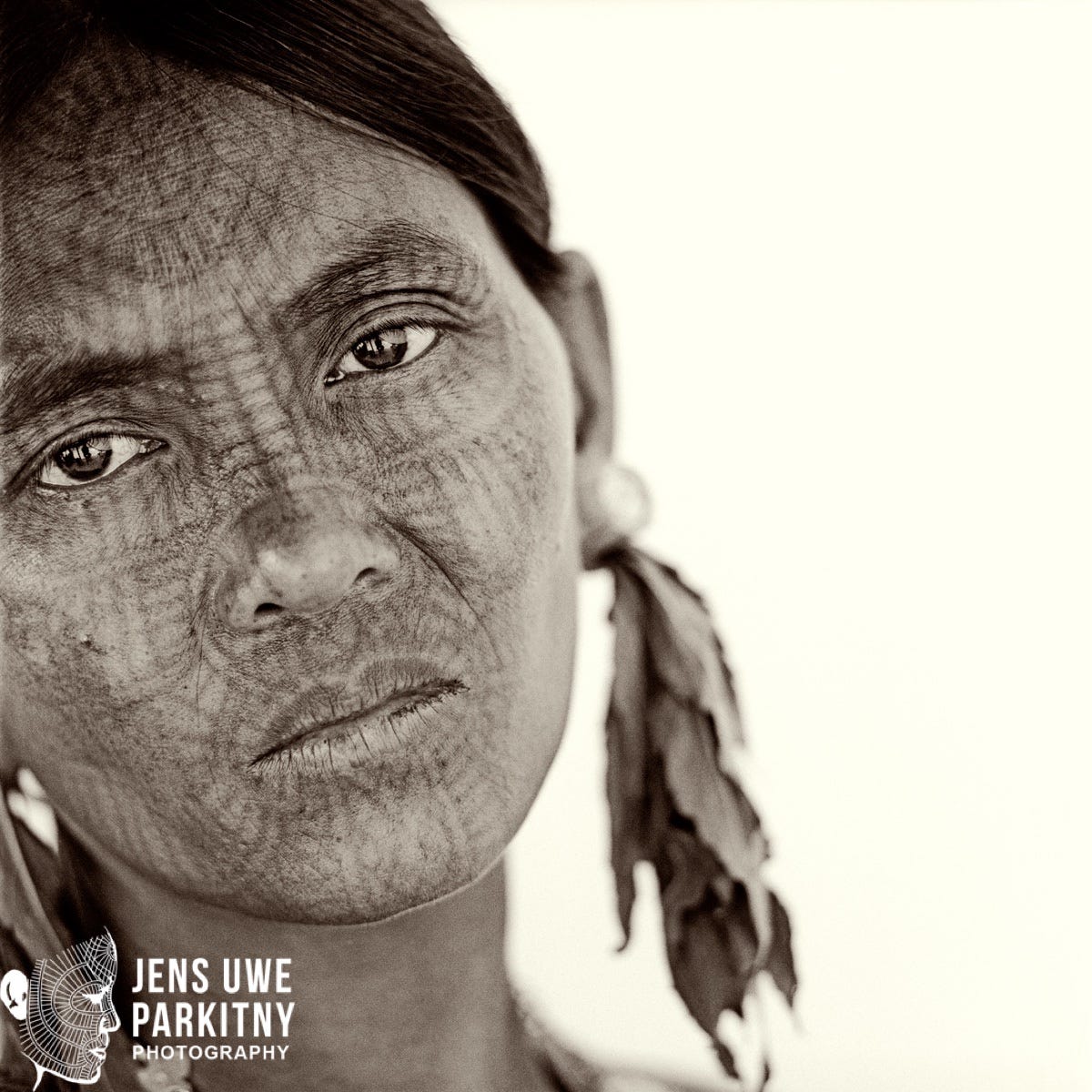

The untold story of beauty and identity of Myanmar'south Southern Chin Women — and a myth unraveled

by Jens Uwe Parkitny

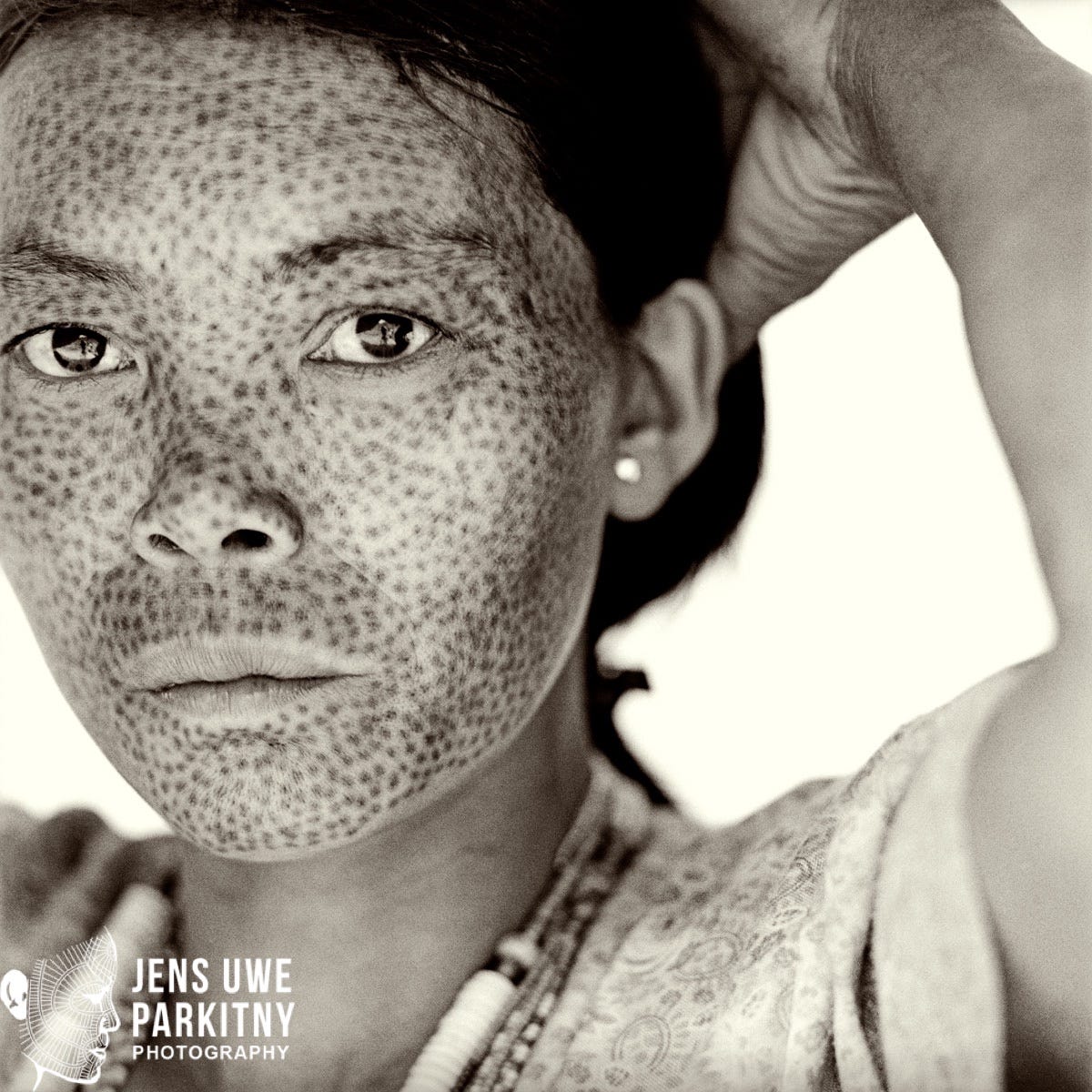

Their dazzler is mythical and how the Chin women lost it became a legend. Often told, it features all the typical characters that brand up a good story: pretty, young, innocent girls that live in the forests upon the hills and an evil king that lives in the plains and sends out his men to raid their villages, in search of the most beautiful females. In guild to stop the abduction of their girls and women, the Chin communities that were exposed to the marauding troops started to "mark" the faces of the young girls, one time they reached puberty. With rattan thorns, symbols and patterns were "tapped" into the dermal tissues of the face up to deliberately destroy their cute advent. The male monarch soon lost interest and his men were never seen over again in the villages. The tattoo tradition, however, lived on, until adequately recently: in 2005, I met a young Laytu Chin woman with a cute facial tattoo, in the hinterland of Western Rakhine. She was 17 years old and only tattooed five years earlier. She never heard of that king-raiding-Chin-villages story for beingness the reason of her tattoo, past the way.

Historically, there is no evidence existent up until today, that any of the kings ruling in the territory of today's Myanmar has systematically raided Chin villages in the plains or in the mountains.

Information technology is the well-nigh common storyline of almost every one-half-hearted explanation of why the women of certain Chin groups that dwell in Southern Chin Land, Western Rakhine and in a few villages and towns in Magway Division started the do: to brand themselves "unattractive" to outside intruders. The rex, of class, is portrayed as a Bamar king in about hearsay, and the whole story therefore has a political dimension and reflects a victimized viewpoint. Historically, still, there is no evidence real up until today, that whatever of the kings ruling in the territory of today's Myanmar has systematically raided Chin villages in the plains or in the mountains.

Equally a matter of fact, quite the opposite seems to be true. The British commissioner Edward Tuite Dalton, made in charge of the classification of Bengal'southward and Assam's ethnic groups during the second one-half of the 18th century, thus, reported that the enslavement of women and children of other tribes was quite common amidst the Kheyngs [Chin] and related groups in Arakan's [Rakhine State] heartland: "The men get killed, the women and children are abducted and forced into slavery" (Dalton 1872, reprinted in 2007). Alice M. Hart, also known every bit "Mrs. Earnest Hart", second wife of British journalist Ernest Abraham Hart, wrote about "the savage" Chin, after a trip to Burma in the spring of 1895, that they were "constantly occupied with raiding the lowlands to obtain cattle and spoils too as Bamar women and children, who were kept as slaves, but were seemingly treated well" (Hart 1897).

The Deputy Commissioner of British Burma and late Superintendent, Major Westward. Gwynne Hughes, who was actually stationed in the Arakan Hills from 1871 till 1880 (except in the years 1875 and 1876), observed that "the Chins of the Arakan hills are far wilder and more retiring than any other of the tribes…"(Hughes 1881).

All cultures, that practiced or still practice facial tattooing in i form or the other, perceive information technology equally "cute", as "dazzler enhancing" and "status elevating" rather than "defacing".

The widespread myth nearly the Chin women and their facial tattoos has 1 other very pregnant flaw: a story view-point of a beauty ideal that is inline with mainstream western civilization, where a facial tattoo is nonetheless considered a taboo and is not widely accepted. "They made themselves ugly to deter the king from kidnapping them…", is the common proverb — and the common fault.

All cultures, that practiced or still practice facial tattooing in one form or the other, perceive information technology equally "beautiful", as "beauty enhancing" and "condition elevating" rather than "defacing", concludes Dr. Lars Krutak, a world leading tattoo anthropologist (Krutak, 2007).

Other experts such as the late anthropologist F.K. Lehman casted doubt on this "nosotros-made-ourselves-ugly"-theory as well, because "Chin people believe the tattooing does not disfigure but enhances their beauty." (Lehman 1963)

The Southern Mentum groups in Myanmar would therefore have been the only ones worldwide, introducing female facial tattooing for a defensive purpose, an "ugliness-sation"-strategy for their entire female stock, so to speak. And that simply doesn't make sense, if compared with what is known about other tribal groups that still practice or have adept the permanent "mark" of the faces of their young women through tattooing or incision. The practice was widely spread amidst hill tribes beyond Asia and could be found on all continents where humans settled (Krutak 2007).

Major Westward. Gwynne Hughes observed: " In accord with the custom of all tribes of the Mentum family, the faces of their women are tattooed, the matter being washed as a rule with some ceremony at the age of puberty."

Hughes was familiar with the reasons that other writers earlier him attributed to the practise of tattooing amongst the hill tribes:

(1) in order, past disfigurement, to forestall their women being carried off to the harems of the Burmese high officials;

(2) to enable to recognize their own women carried off in raids, and to conceal the women of other tribes carried off by them"

For him, this reasoning was non conclusive at all, because if "…either theories rested in satisfactory grounds, information technology would be reasonable to suppose that other adjoining tribes would besides take adopted the custom, though on the score of female dazzler, which is as lamentably conspicuous by its absenteeism amid the Chins every bit amongst the hill tribes more often than not, there is certainly no cause for resorting to the practice as a means of preventing their women being carried off as concubines to the Burmese Courtroom. "

Despite the fact that his remarks on Chin womens dazzler perceptions are not just non-politically correct in post-colonial times and rather reflect the British Empire view and attitude, just too incorrect: merely look at some of the young Chin women and how attractive the tattoos make them expect! It is remarkable though that he comes up with his own theory of why Mentum groups dwelling in regions adjacent to those of the "Bama", practiced facial tattooing.

Major Hughes: "… it seems to me most probable that tattooing was adopted by them in simulated of the Burmese, and not especially invented for the purposes indicated in the to a higher place two theories; for against the acceptance of either stands the fact that there are no greater raiders than the tribes bordering these Chins, viz., Shandoos, Kamees, and Upper Pin Mroos, none of whom practice tattooing." (Hughes 1881)

The practice serves circuitous purposes that can only exist fully understood when looking into all aspects of culture as well as social-interactions and functions within the group and their traditions and believes. Facial markings and other body modifications in tribal societies are literally "Marks for Life" that helps a particular grouping to stick together, to function orderly and to survive in harsh environments.

Facial markings and other body modifications in tribal societies are literally "Marks for Life" that assist a particular group to stick together, to office orderly and to survive in harsh environments.

Each and every pattern of a facial tattoo among the different Chin groups is therefore a visual expression of belonging and identity, of the ability to endure pain, of having mastered different stages in live, of being a full member of the community with duties, privileges and status, of a particular beauty perception and — last not least — of a certain spiritual and super-natural believe. Afterwards all, a facial tattoo is like a permanent mask, and, while ritually applied, this mask is super-charged with protective charms that are meant to defend off evil spirits, in life — and mayhap even in the afterlife. (Krutak 2007; 2012). Some groups of the Naga, linguistically related to the Mentum, believe that their ancestors cannot recognize them if they do not behave the ancient tattoo marks on their face and forehead (Saul, 2005). It is therefore possible that some of the Chin groups followed a similar believe.

The beginning known portraiture of a Chin woman with a facial tattoo was published in 1800 by Major Michael Symes, who was sent on a mission to Burma by the Governor-General of India, Sir John Shore, in order to secure protection for British subjects from the Emperor of Ava, King Bodawpaya, in 1795. Together with a support crew including a botanist and a painter, he traveled the kingdom and wrote a detailed account of his feel and included many illustrations of monuments and people (Symes, 1800).

Already more than than 200 years ago, the pregnant and purpose of the facial tattooing was non a knowledge that was preserved among the Mentum.

It was on November the 9th in 1795, probably one of these "Burmese days", with an impeccable blue sky, that he met a "Kyan" [Mentum] woman with a full facial tattoo and asked his painter to make a drawing of her and her husband, both dressed in their typical attire. This see made a lasting impression on him: " …but the nigh remarkable role was her face, which was tattowed all over in lines more often than not describing segments for circles. This ceremony, which in some other countries is performed on the parts of women not publicly exposed, among the Kyan is confined wholly to the visage of their females, to which, in the centre of an unaccustomed beholder, it gives a most extraordinary appearance….". He asked the origin of the custom and recorded that "…this they did not know, but said it had existed from time immemorial, and that it was invariably performed on every female, at a certain age." In other words: already more than than 200 years ago, the pregnant and purpose of the facial tattooing was not a knowledge that was preserved among the Chin. The practice, I assume, is therefore older than a few hundred years and might even date back a 1000 years or more than.

Non much is known nearly the Chin tattooing ritual that was practiced by around half (as estimated by the author) of the 53 officially recognized Chin groups in Myanmar. Assuming that Southern Mentum groups that got in contact with colonial administrations too as with Buddhist and Christian missionaries, stopped the practice sooner rather than later. Some of the groups that practiced tattooing seem to have already vanished. In 1906, Sir J. George Scott described a tattoo design consisting of " tattooed horizontal lines across the face" for a Yindu group that already ceased to exist (Scott, 1906). Also, the facial tattoo of "lines generally describing segments for circles" that Major Michael Symes spotted on a Chin woman in 1795 is not a hallmark of any of the known Mentum groups today.

I cartel to speculate that all groups that settled in Southern Chin Land and Rakhine skilful facial tattooing and that includes all Ashö Chin groups.

Experts on indigenous tattoos, such equally the American tattoo anthropologist Dr. Lars Krutak, believes that the "marker" of a girl was celebrated in a fashion similar to that of the Naga People, who alive further North of the Chin (Krutak 2009): with the sacrifice of a mithun (Bos frontalis), a domesticated cattle or gaur that plays a significant role in offering rituals among all ethnic groups of the mountainous regions in Northeast India, Eastern Bangladesh and Western Myanmar, including Chin and Naga people.

Forehead and cheeks are tattooed commencement. Pricking the part effectually the rima oris comes next. The eyelids are done at final and it is a very delicate piece of work that requires utmost concentration and adroitness.

U Bhutaung , a devote Christian Yindu Dai man that lives with his two (facial-tattooed) wifes in Hlaing Doh hamlet, explained to me elements of the tattoo ceremony in 2014: it all begins with welcoming the tattoo master at abode early in the morning, at sunrise, and nowadays him a white chicken in order to get him into the correct mood. Freshly cutting rice paddy and a chicken egg are placed by his side to please the spirits. If too much blood is dripping downwardly the face up of the girl that is existence tattooed, the egg is rolled over the intense haemorrhage section to stop the bleeding. Brow and cheeks are tattooed first. Pricking the part around the mouth comes next. The eyelids are done at last and information technology is a very fragile work that requires utmost concentration and craftsmanship. Information technology's rare that Yindu girls were able to sustain hours of tattooing and though some did, the majority did information technology in stages. Every bit Lucian and Christiane Scherman correctly stated already in the beginning of the concluding century: "The procedure started at an early age and oft lasts a number of years." (Scherman 1922)

In fact, within some of the groups (ie Yindu Dai and Hmoye), information technology was allowed to do the tattoo in phases of up to 2 years or longer. The determining cistron was the pain threshold of each woman. Some of the women I spoke to underwent up to 10 sessions inside a yr to complete the tattoo. Others, such equally the Laytu, didn't allow their girls to have a choice and they were stock-still on the ground then that the tattoo master (females but so information technology seems in the instance of the Laytu; male person and female in the case of the Yindu and Ubtu) could do the piece of work in one single session that could last upwards to eight hours. Yindu tattoo masters that completed a full facial tattoo were rewarded highly: five arrows, one cotton fiber blanket, i glass beads necklace, one basket full of raw cotton and one cotton fiber brawl. Other Mentum groups such equally the Ubtu paid with Indian Silver Rupee coins also as with food and free-flow of millet wine.

Interestingly, the tradition of female person facial marking is just constitute among those Chin groups that settle in the Southern parts of Mentum State, in the West of Rakhine, item along the Lemro River, and in the neighboring areas of the Magway Administrative Division. Neither the groups in Northern Chin State nor those that alive in Bangladesh (where they are called "Zo") or India are related to the custom. Why this is the case and why this tradition has evolved and connected to survive but in a fairly small region within Myanmar upwardly to the terminal decade defies any scientific explanation.

This is also true of the symbolism used by the various groups, which includes dots (Matu Chin), patterns made up of vertical lines and dots (Yindu Dai, Ng'Gaah), rune-similar symbols (Mün), more complex, mandala-like designs (Laytu, Hmoye, M'Khan, Sungthu, Sutu or Songlai) and even completely blackened faces (Utbu or Ubun). So far, scientific interpretations of these symbols accept been successful only to a very limited extend. They are based on comparison with figures, ornaments and shapes that observe a use in the textile culture of different groups, such as in the outstanding woven textiles which are highly appreciated by collectors and museums. The Y-shape like rune tattooed on the forehead of Muen Chin Women (Mindat and Kanpelet townships) might be a directly reference to the Y-posts used by the very same Chin group in brute scarification rituals. Suhtu (Sone-Glai), Laytu (Laitu) and Sunghtu (Sone-Tu) take a sun like symbol tapped on their forehead, with fine lines radiating from it, covering the entire forehead. The tattoo tradition and rituals certainly date back to times where the respective Chin groups operated within an animistic conventionalities system and worshipped nature spirits. The sunday might have played a ascendant office in this.

One also has to admire the craftsmanship of the tattoo masters that applied complex patterns and customized them to the individual features of a young woman's confront. I only met one living, female person Laytu Chin tattoo master ("Sayamah") in a small village called Taung Gyi in Western Rakhine in 2005. According to her, she stopped the tattooing 10 years earlier, in 1995. Though she knows the pattern, she didn't know the pregnant of it, except that the round, crossed circumvolve on the forehead represents the sun. Its perfectly round shape is drawn with a bamboo or money. Interesting to note that her own daughters, teenagers at the time, had no tattoos and preferred to apply lipstick and Thanakha, the grinded bark of the Thanakha tree (Limonia accidissim), mixed with water to a paste and applied on the cheeks, to heighten their beauty.

If Chin women are asked about the specific meanings of their tattoos, they normally answer "considering it makes us cute" and "because all the other women in our village take them as well" or simply "considering it is our tradition". Since only oral history was used among the various Chin groups to transfer myth and knowledge, the specific meanings of the unlike tattoo patterns and symbols seem to accept gotten irretrievable lost over fourth dimension. The exact meaning of their "Marks for Life" therefore remains a mystery.

Source: https://medium.com/@jensuwep/marked-for-life-9c9774ae79e8

0 Response to "Marked for Life Myanmarã¢â‚¬â„¢s Chin Women and Their Facial Tattoos Review"

Post a Comment